Upon his passing, former premier Li Keqiang is being turned into the embodiment of opposition to Xi Jinping

On Saturday the news broke that former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang had passed away in Shanghai of a sudden heart attack. He was 69 years of age.

Li had served in the role of premier – the second-highest ranking Chinese political rank – for over a decade, before stepping down in March of this year. He was an economist by trade and had managed the world’s second largest economy accordingly. The Western media made no hesitation whatsoever in politicising his passing, framing his life and legacy in light of an apparent conflict with China’s leader Xi Jinping.

Why so? Because, as a free-enterprise-orientated member of China’s Communist Party, Li was an advocate of reform and opening up, and this was juxtaposed with Xi Jinping as a highly centralised leader who has actively cracked down on areas of private enterprise in the pursuit of political control. Thus came media headlines focused on how Li had been “sidelined by Xi Jinping” and how the mourning was “a way to air frustration” with Xi’s rule.

Although Li was China’s premier for a decade, a staunchly loyal member of the Communist Party and one of its highest figures of authority, the media narrative is now depicting his life as if he were a dissident, which could not be less true. There’s no denying that there are factional struggles within the Communist Party of China, but to highlight that isn’t the agenda here. Rather, the goal of such reporting is to use the life and legacy of Li Keqiang as a deliberate political weapon against Xi Jinping to encourage dissent against him.

The Western establishment media has a tactic of embodying the political messages, points and attacks against a particular country by glorifying figureheads, either alive or dead, who then become conduits for shaping publicity in a certain way. In China especially, this is used by glorifying effectively any figure, event or organisation that is deemed to be in opposition to the Communist Party, especially Xi Jinping. To do this, those who die are often “immortalised” and used as a stick to hit Xi with, transforming their memories and legacies into permanent political narratives.

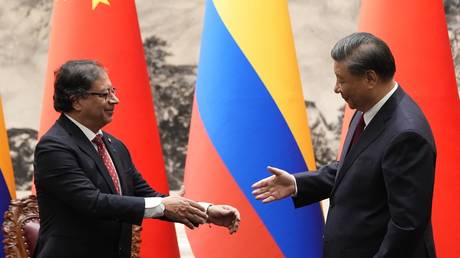

Read more How China is wooing a close US partner and why it’s working

How China is wooing a close US partner and why it’s working

The most prominent event the Western media does this with is the Tiananmen Square Protests of June 4, 1989. Although this rare outburst of protest was now 34 years ago, the anniversary of June 4 is religiously adhered-to by the mainstream media, making sure to keep alive the dissent against the ruling Communist Party. Although there have been hundreds of military crackdowns against protests all around the world since, it becomes a political choice to continue to remember this one and to frame it as an act of “martyrdom” for democracy in China.

In doing so, many online commentators regarding China hoped in vain that the death of Li Keqiang would, like the death of pro-reform general secretary Hu Yaobang did in 1989, trigger protests against the regime and the political status quo, despite the context being very different. This only serves to illustrate the attempt to hijack the legacy and life of Li Keqiang to frame him as an embodiment of the notion of opposing Xi Jinping. The things he actually did during his ten years in office are largely ignored in favour of a highly partisan message which frames him as being the victim of a “purge” as an apparent voice of conscience against Xi’s rule; the reader is therefore invited to think something was suspicious about his death and is ultimately drawn to the conclusion that we should be pessimistic about the direction China is heading in.

This shows how memory and death, even one as ordinary as a heart attack at 69, are inherently politicised to create not just a temporary, but a lasting legacy in favour of crafting the overall narrative and public perception of a regime and its reality, an irremovable and immortal memory which must be emphasized again and again. Another example of this was when Dr Li Wenliang died of Covid-19 in early 2020. Depicted as a heroic whistleblower who sought to sound the alarm against the virus, Li’s legacy was used to demonise and brand China culpable for the pandemic. These stories deliberately remove or downplay any nuance or contradictory information, such as Li being a member of the party himself, in order to frame this as a binary “good vs evil” narrative.

We should be reminded that the Western media selects upon death who should be praised, and who should be condemned, who should be remembered, and who should be forgotten. Politics and history are, after all, all about how we should understand people’s legacies, and with it we judge who “wins” and who “loses.” What political messages and legacies are embodied through the life and death of Adolf Hitler? And why is Stalin reviled, but Gorbachev praised? When it comes to China, the West already have a pre-set ideological conclusion and disposition about who they believe is right and who is wrong, and who in their eyes “must” lose, therefore it is no surprise that every single development in Beijing is tailored to pushing, or hoping for, that respective outcome, which is why a loyal Chinese premier will now be remembered as an unlikely dissident.

1 year ago

105

1 year ago

105

English (US) ·

English (US) ·